- February: 300,000 in Pennsylvania

- March: 800,000 in Michigan

- July: 2,300 in the Outer Banks of North Carolina

- September: Millions in Houston, Texas and large swaths of Florida, the Caribbean, and Puerto Rico

- October: 1.2 million in the Northeast

These are the states and number of people who have been affected by power outages caused by damaged power lines this year – and that is certainly not all of them, just the highlights. These were enormous, costly events, which are increasing in frequency and underscore the need for a better way to deliver electricity to the public.

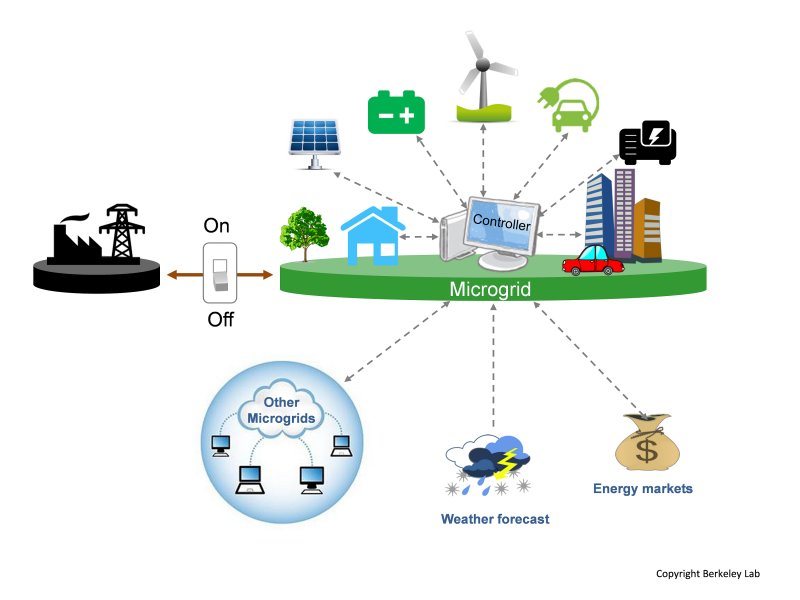

To date, microgrid uptake is slow. Soam Goel, Partner at Anbaric Development Partners explained during the conference that micrgorids are on the cusp of the “early adopter” phase but added that adoption has been growing tenfold every year. What’s holding them back? Microgrids require not only new technology and equipment, but utility adoption of them would require a whole new set of regulations and policies, not to mention money. Another obstacle to adoption is the fact that the technology is not standardized. According to Goel, “if you have seen one microgrid, you’ve seen one microgrid.”

For now, the technology is mostly finding homes in the MUSH markets — military, universities, schools and hospitals — because these markets inherently have additional drivers for microgrids. For the military, contained microgrids bring energy independence and better cyber security; for schools and universities, clean energy microgrids are good avenues to reach sustainability goals; and for hospitals the driver is reliable power that never goes down.

Further, a few-forward thinking states are starting to consider microgrids as alternatives to traditional utility upgrades.

The Marcus Garvey Village Microgrid

Doug Staker, a VP with Demand Energy Networks (DEN, an Enel company) presented during the conference, showing how his company arrived at its Marcus Garvey Village microgrid project in Brownsville, New York, which was at the heart of a constricted area in Con Edison’s territory. The utility had a substation that was going to be short by 53 MW of transmission capacity by the summer of 2018, said Staker. Con Ed proposed a $1.2B plan to upgrade the transmission line. Staker explained that the NY public utility commission thought that Con Ed’s $1.2B for 53-MW transmission line for a 48-hour problem was not a good solution and instead authorized $200M to find another way to solve the problem.

That authorization resulted in a 300-kW/1.2-MWh storage system plus 440 kW of solar capacity and a 400-kW fuel cell. The Village’s owners, L+M Development Partners, and Demand Energy agreed on a “shared savings” operating model, according to DEN, which covered debt service and allowed the two entities to share in revenue generated. L+M made no upfront investment to install the system.

A New Way Forward for Utilities and Regulators

For now, projects like the Marcus Garvey Village microgrid remain few and far between despite the overwhelming evidence that the grid system in the U.S. is vulnerable in many different ways. But Staker thinks that might be changing for a few reasons. First, he’s hopeful that utilities are beginning to consider microgrids as non-wires alternatives because of their ability to shape load and therefore avoid costly transmission upgrades.

“One of the things about grid-connected microgrids is we have the ability to create load with the storage at night and then we are able to take and time shift and manage that load to manage the building load or manage that network load,” he said, adding that when you flatten a load, it improves the overall efficiency and reduces the need for transmission upgrade.

He pointed to a utility in Canada that is looking to avoid building a new transmission line, which is estimated to cost $1M to $2M per mile. Another New Zealand utility needs about 4 MW of storage and about 1.6-MWh of energy to defer a 70-km, 110-kv transmission line, said Staker.

“We think for a $5M investment in technology for peak shaving and microgrids in distributed areas, you can solve that problem very cost effectively,” he said.

Microgrids also solve resiliency issues, a word that has been in the energy news a lot, lately. Staker said his company is talking with a utility near the Great Lakes that is worried about forest growth around distribution lines. Despite its very good vegetation plan, the utility cannot stop the trees from growing taller and older, with some more than 100 years old.

“In a wind storm or ice storm [large trees] fall over and take out that distribution line and typically when they take those types of lines out, not only do they just take the line out, but they take poles out. And whenever you take poles out, that’s multiday outages,” said Staker.

He said that this particular utility is looking to see if microgrids make sense in those remote areas where they could keep power running to one gas station, one grocery store, one hospital and one police station in the event that a distribution line goes out.

“I think you are going to see more and more utilities look to build that infrastructure or do like Con Ed did with us and incent private developers to go out and build them,” he said.